Chapter 1: Introduction to Primary Care Systems Thinking

Understanding UK Primary Care as a Business Entity

Primary Care in the UK is the first point of contact for most patients seeking medical attention. It plays a vital role in managing chronic conditions, preventive care, and acute illnesses.

To operate efficiently, GP practices function like businesses, managing resources such as staff, equipment, and funding from the NHS. GP partners enter contracts with NHS England, and the ICBs commission primary medical services under those contracts, with the aim of providing effective management that ensures quality patient care, staff well-being, and financial sustainability.

Importance of Demand & Capacity Management

Balancing demand (patient needs) with capacity (available appointments, staff, and resources) is the bread and butter of the GP practice partnership.

Describing what you offer to patients combines both art (experience) and science (concepts).

Getting it right for each practice population is critical to avoiding delays in patient access, reducing inefficiencies and waste, and preventing poor patient outcomes where applicable. When demand exceeds capacity, patients face longer wait times, leading to dissatisfaction and potential health deterioration. Proper demand and capacity planning helps optimise service delivery.

The rest of the article offers the concepts that can facilitate demand and capacity analysis in primary care.

Chapter 2: Primary Care Systems & Operations

Core Systems in Primary Care

The best way to approach the primary care landscape is to think in systems. Primary Care systems consist of administrative, clinical, and operational workflows. These include appointment scheduling, triage, consultation processes, prescriptions, and billing. This framework enables an easier appraisal of the practice that is devoid of guesswork and makes it easier to identify bottlenecks that hinder a desired goal.

Furthermore, much of the progress observed in primary care has been born out of experiential learning. However, this valuable knowledge is at risk of being lost as experienced GP partners retire, and there are fewer GPs motivated and incentivised to take on practice management roles.

While this practical knowledge can be shared when you join a partnership, the underlying scientific principles of managing a GP business should be taught during the GP vocational training scheme and thinking in systems underpins this mental model of thinking.

So, how does “systems thinking” work in primary care?

We would explore this further using challenges of demand and capacity in primary care and suggest how the integrated systems in primary care work together to produce a profitable and efficient practice.

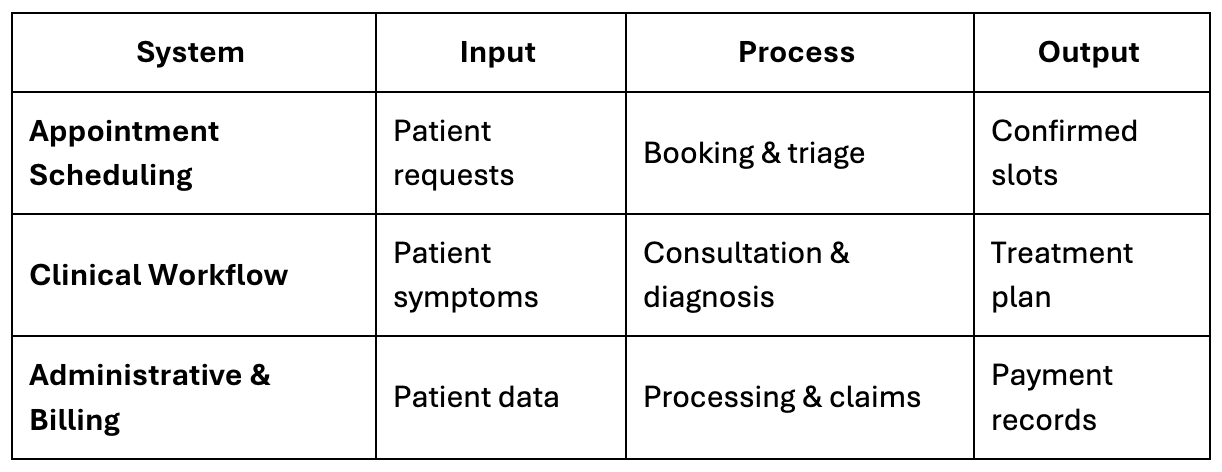

Inputs, Processes and Output

There are typically three parts of a system: Input, process, and output.

Let’s use this table to illustrate each component.

While input is simply what is coming into the system, the process requires operating procedures to materialise.

To be successful, each of these systems should have standard operating procedure. SOPs provide clear, step-by-step instructions to ensure efficiency and consistency in handling various tasks within primary care.

Example:

- Appointment Scheduling SOP: Define steps for triage, allocation of appointments, and handling emergency requests.

- Medication Refill SOP: Outline how repeat prescriptions are processed, including safety checks and approvals.

Finally, an output would be the desired product of each process.

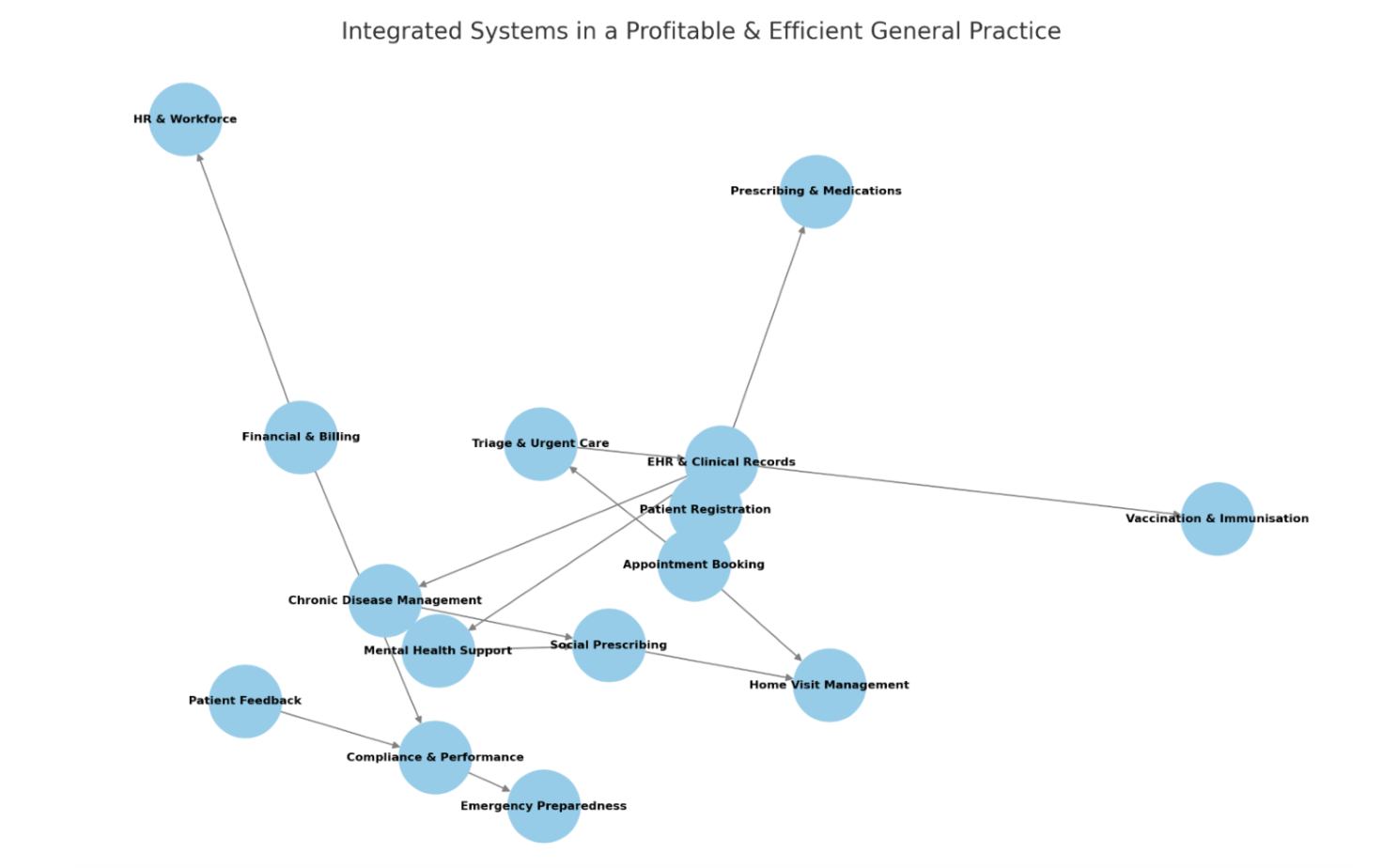

System Interactions

Here is a Systems Integration Flowchart illustrating how different primary care systems connect to create a profitable, efficient, and compliant general practice.

Fig. 1 Flowchart Illustration Showing System Integration

A well-run GP practice depends on good patient records. Electronic Health Records (EHRs), with the most commonly in use being SystmOne and EMIS, are the centre to store patient information, help clinicians make informed decisions, and keep everything running smoothly.

However, to make sure patients get the best care without unnecessary delays, sub-systems like triage and appointment booking, finances and compliance links, billing, managing human resources and following NHS rules are just as important to keep the practice sustainable.

Additionally, unexpected challenges, like staff shortages or emergencies, can happen at any time, resilience planning ensures the practice stays stable and ready to handle whatever comes its way.

It is expected that practices should already have this level of system integration operationalised to be considered viable. The real benefit lies in activating and optimising any dormant systems or subsystems, but you need data to achieve that.

Chapter 3: Data-Driven Decision Making

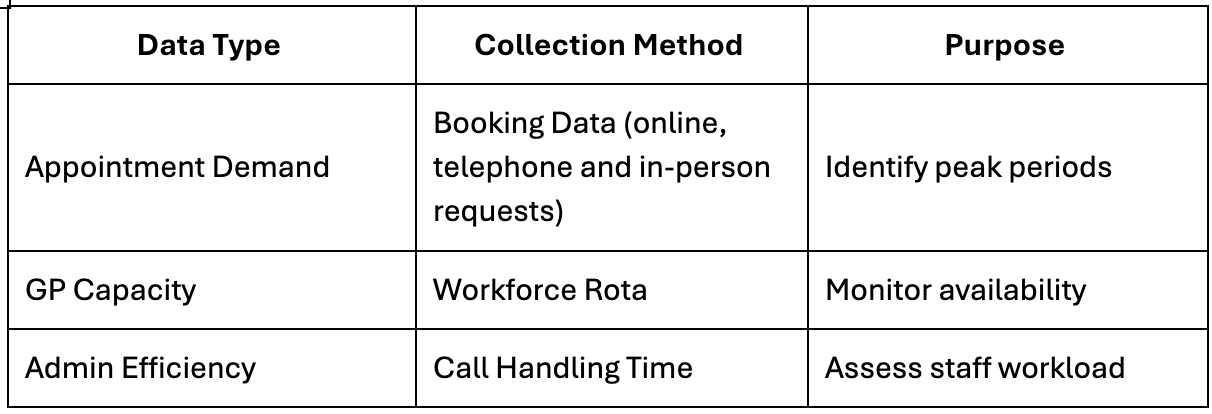

Designing Data Collection Frameworks

If you do not think in systems, you may well be guessing at where the problems that are affecting efficiency, safety and profitability lie. Collecting and analysing data allows practices to identify trends, bottlenecks, and areas for improvement.

The following table outlines key data points:

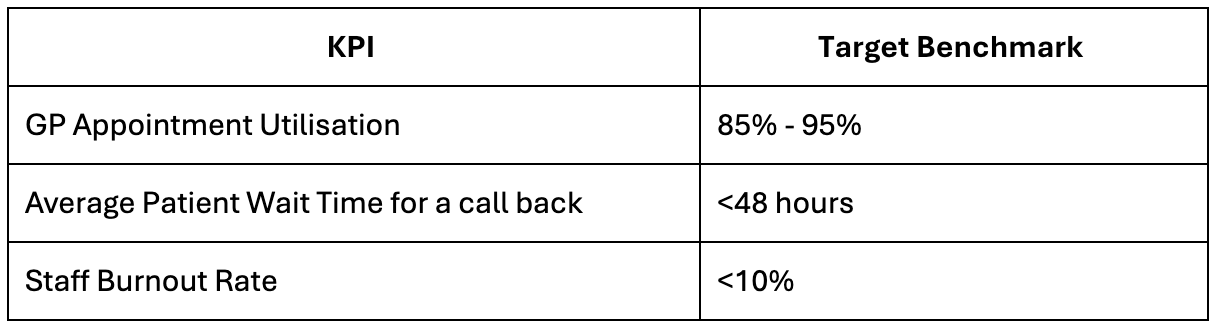

KPI Development & Benchmarking

Practices are constantly balancing demand and capacity. Notably, specific empirical threshold values for peak demand indicators in primary care are not explicitly defined in NHS contracts. However, several authoritative sources like the BMA, provide recommendations and insights that can inform the development of such thresholds in practice. There are three areas where there is some benchmarking that can allow for suggestions to be made for key performance indications for real world practice.

- Safe Working Limits for GPs:

The British Medical Association (BMA) suggests that a safe level of patient contacts for a GP is not more than 25 per day.

Practices are encouraged to move to 15-minute appointments to enhance the quality of care and reduce the need for repeat consultations. Read more here.

- Telephone Access and Response Times:

High-quality telephony systems are essential for modern general practice access models. While specific response time thresholds are not detailed, practices are advised to optimise their telephony systems to manage patient demand effectively. Read more here.

- Aligning Capacity with Demand:

NHS England provides guidance on understanding and managing demand and capacity in general practice. Although specific numerical thresholds are not provided, the emphasis is on building data collection and analysis capabilities to identify and address demand-capacity mismatches. Read more here.

More recently the push for total digital triage would facilitate data collection and analysis of demand and capacity.

Due to the lack of explicit numerical thresholds in these guidelines, each practice should establish its benchmarks against specific key performance indicators (KPIs) based on patient population, available resources, and historical data.

It is advisable to regularly review and adjust these thresholds in response to changing circumstances, and contracts and in consultation with relevant local health authorities.

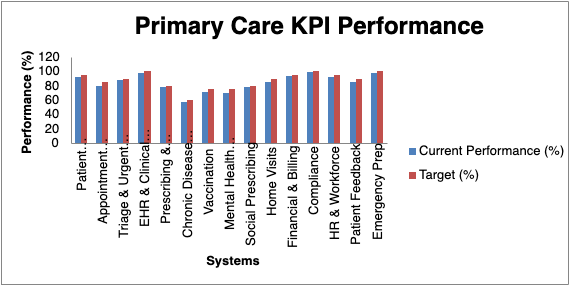

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) help track the efficiency and effectiveness of practice operations.

Dashboard Visualisation

A well-designed dashboard provides real-time monitoring of demand, capacity, and other performance metrics. Visualising data in these formats is easier to digest and can stimulate discussions for improvement and point out areas to celebrate.

Fig 2: Diagram of Sample Dashboard Visualisation

Chapter 4: Winter Pressures & System Dynamics in Demand and Capacity Analysis

To fully understand the demand and capacity dynamics in the primary care system, let’s break it down into resources, inputs, constraints, and the feedback loops that regulate and sustain the system.

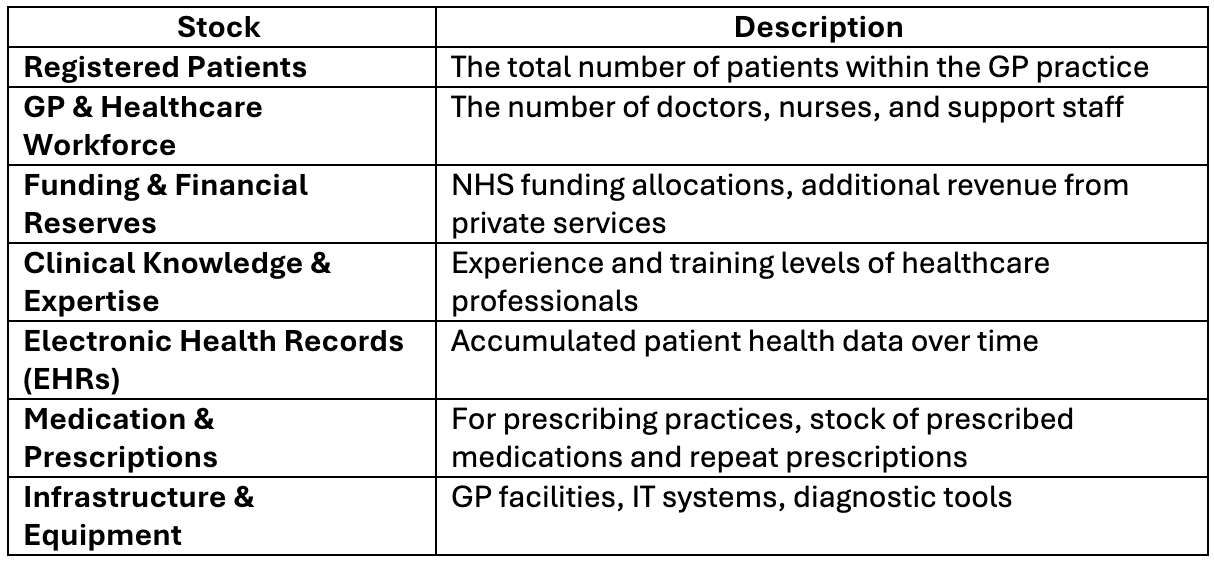

1. Stocks in the Primary Care System

Stocks are the accumulated resources within the system that influence its function over time. In primary care, these include:

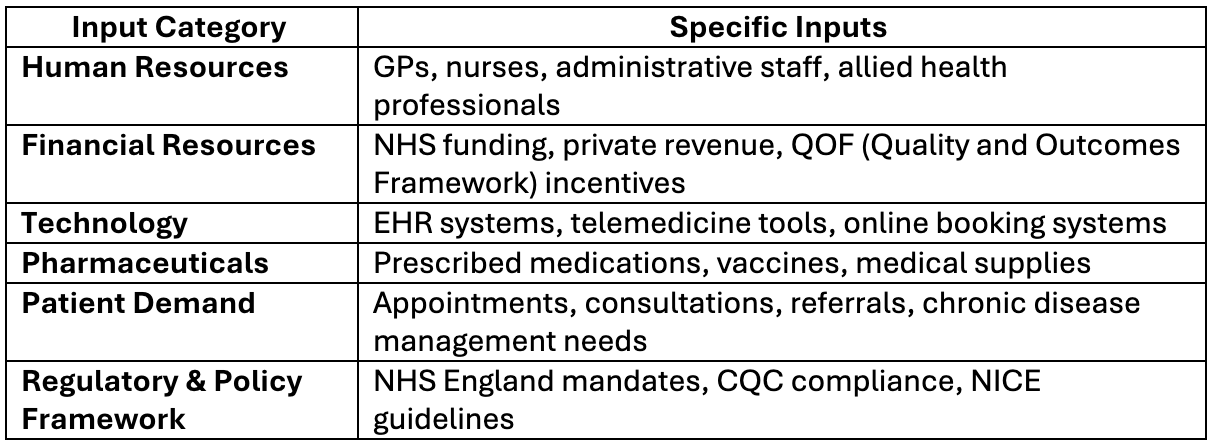

2. Key Inputs into the Primary Care System

Inputs feed the system and enable it to function. For example:

3. The Most Limited & Critical Input

The Most Limited Input is the GP & Healthcare Workforce

Why?

- GPs are in short supply due to workforce burnout and early retirement.

- This is compounded by recruitment & retention challenges, particularly in rural areas.

- Increasing patient demand, especially during winter seasons.

- Time constraints also limit patient interactions and quality of care.

Impact:

When GP numbers fall below a critical threshold, access to care declines, leading to longer wait times, potentially increasing emergency admissions, and patient dissatisfaction.

Solution:

- Increase workforce through incentives & international recruitment.

- Expand AI & digital tools to improve GP efficiency.

- Strengthen multidisciplinary teams. These include clinical pharmacists, advanced nurse practitioners, first contact physiotherapists, etc, working in primary care. A lot of investment has gone into these ARRS roles. Read more here.

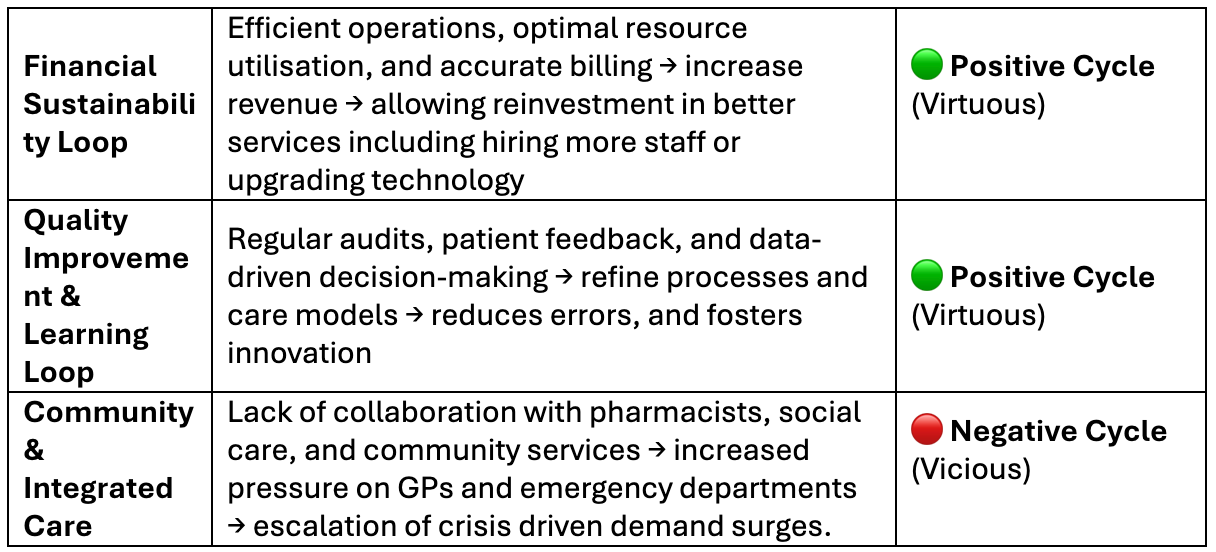

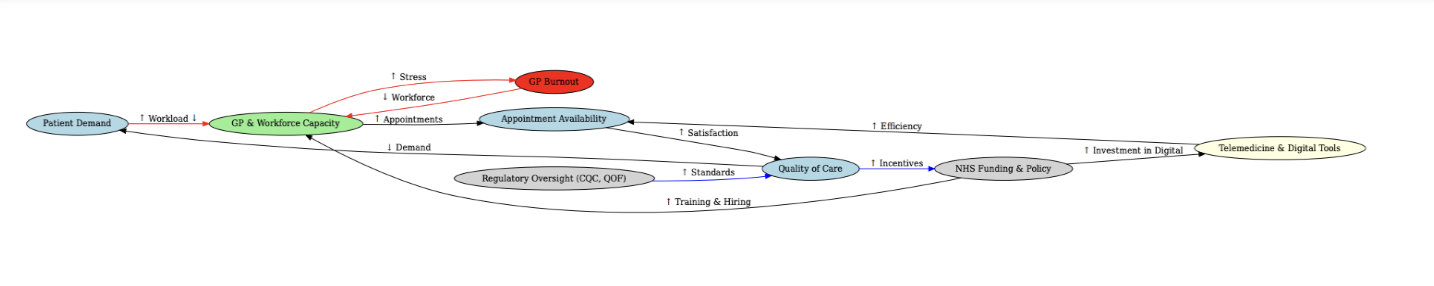

4. Feedback Loops in the Primary Care System

Primary care, like any living system, is shaped by the way different forces interact and influence each other over time. Some forces push the system to grow and expand (reinforcing feedback loops), while others work to keep it stable and prevent it from spiralling out of control (balancing feedback loops). There are also external forces, such as government regulations and NHS policies, that can either support or restrict how the system operates. By understanding how these different feedback loops interact, we can get a clearer picture of why a GP practice responds the way it does to changes—whether that is an increase in patient demand, staff shortages, or new policies being introduced. For example:

(A) Reinforcing Feedback Loops (Amplify Change – “Vicious or Virtuous Cycles”, “Positively or Negatively” reinforcing the system)

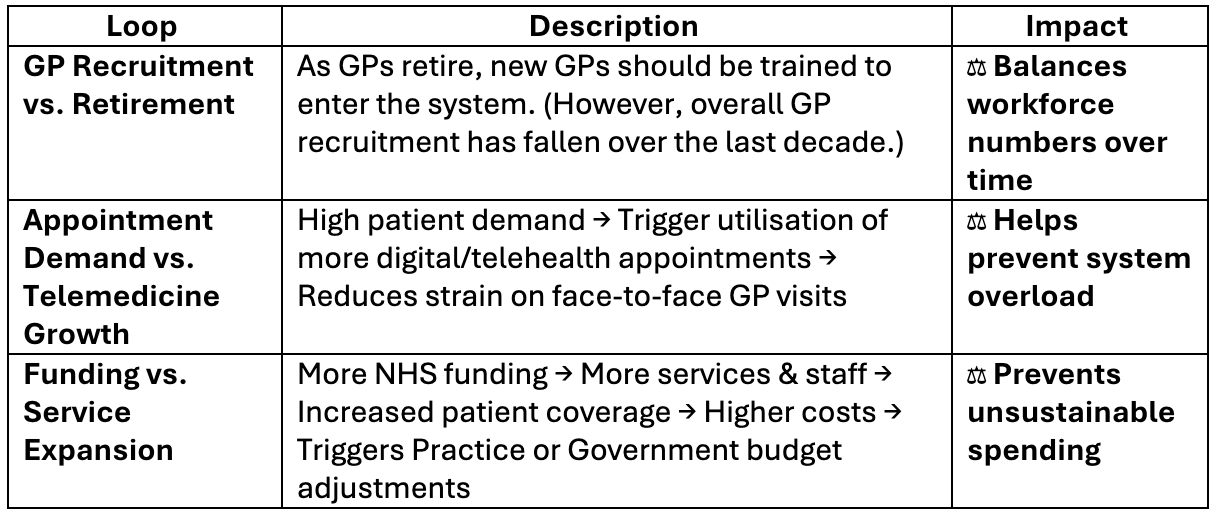

(B) Balancing Feedback Loops (Stabilising – “Self-Correcting Systems”)

(C) Regulatory & External Feedback Loops

Demand vs. Capacity During Seasonal Strains

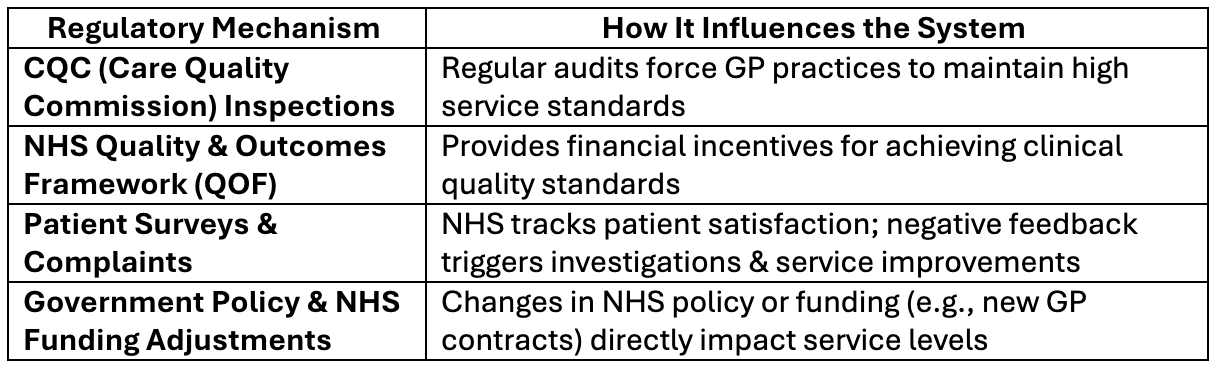

When a GP practice faces stress—like high patient demand during winter pressures—it does not just react randomly. Instead, it follows patterns driven by feedback loops, which shape how the system behaves over time.

Reinforcing loops can push the system toward improvement (such as using digital triage or engaging locum GPs to manage demand) or create a downward spiral (like staff burnout leading to even lower capacity).

Balancing loops work to stabilise the system (like utilising triage hubs or using remote consultations to reduce face-to-face demand), but if they are weak, the practice may struggle to keep up.

By studying these feedback loops, we can uncover why the practice responds the way it does in high-pressure situations. More importantly, it helps identify leverage points—places where small, well-targeted changes (like improving workforce retention) can have a significant impact.

Since the workforce is often the most fragile yet essential resource, strengthening balancing loops that protect staff well-being can prevent a collapse in capacity and ensure the system remains resilient.

Fig 3: Causal Loop Diagram Showing Demand-Capacity Feedback Loops

Chapter 5: Quality Improvement Project: Demand and Capacity Assessment

Setting Aims & Defining Measurable Outcomes

A structured Quality Improvement (QI) project can assess demand and capacity to identify opportunities for improvement. Every QIP must have an aim, family of measures and method of improvement(e.g. PDSA cycle).

On the subject of demand and capacity project aim could focus on understanding, measuring, and optimising demand and capacity in a primary care surgery by collecting real-time data over a set duration of time, identifying inefficiencies, and implementing targeted interventions by the end of a certain timeframe, to improve patient access and GP workload balance. Learn more about how to set a QIP aim statement here.

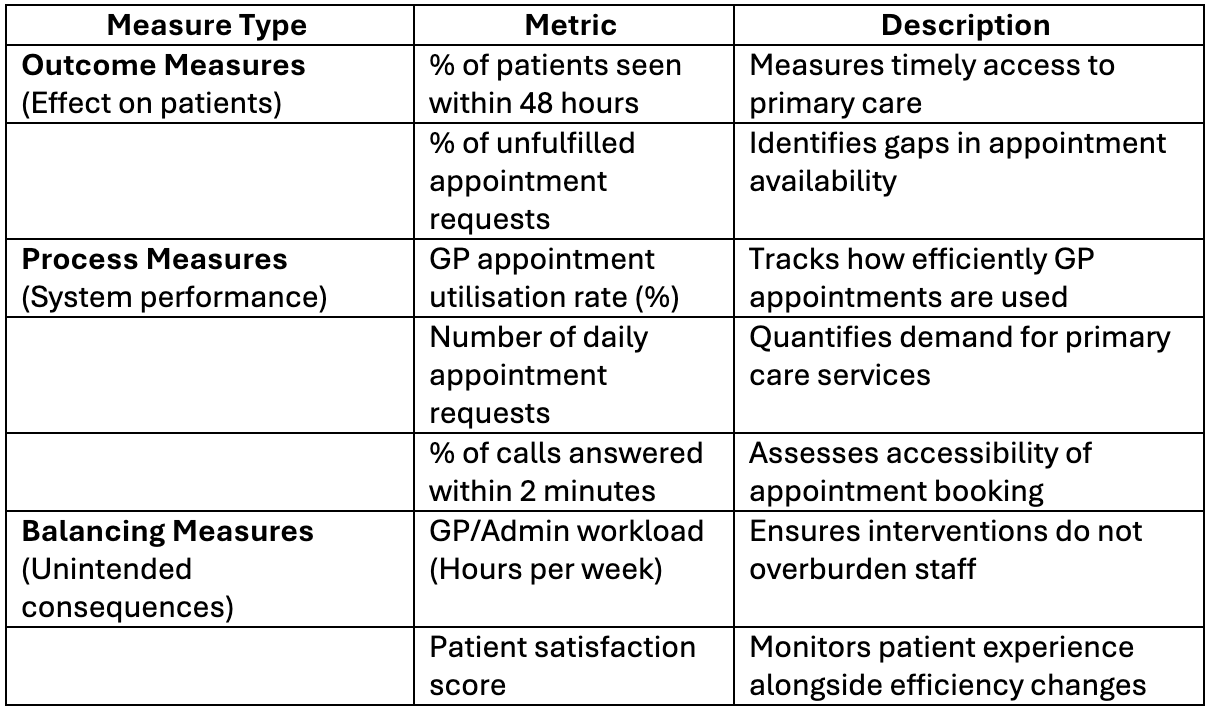

Next is the Family of Measures

There are three types of measures: Outcome measures, Process measures and Balancing measures. See the table below for an illustration.

Applying the PDSA Cycle

A common method of improvement is the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) methodology. It enables continuous learning and iteration to enhance practice efficiency.

Still thinking about demand and capacity see table below for a broad description of each aspect of the PDSA cycle.

PDSA Cycle for Demand & Capacity Optimisation

Plan:

- Collect baseline data on patient demand (appointment requests, call volume, online booking rates) and capacity (GP availability, appointment slots, admin staff efficiency).

- Identify peak demand periods and unmet needs.

- Select an intervention (e.g., increasing telephone triage, shifting some appointments to online/telehealth or diverting to other services, like pharmacies).

Do:

- Implement a small-scale pilot intervention (e.g., introduce an additional triage slot each morning or adjust appointment lengths).

- Use the data collection template to track real-time effects on demand and capacity.

Study:

- Compare pre-intervention and post-intervention data using the identified KPIs.

- Identify improvements, unintended consequences, and patient feedback.

Act:

- If successful, scale the intervention across the surgery.

- If issues arise, adjust the intervention and repeat the cycle.

- Regularly monitor demand vs. capacity using the developed data collection format.

Here is a link to download an excel sheet template for data collection. It has an automated formular to measure the “Peak Demand Indicator (Yes/No)” which is a simple flag to highlight whether a specific period experiences high patient demand that may exceed available capacity. Another formular in the template is Unmet Needs (Unfulfilled Appointments). Unmet needs occur when: Total Appointment Requests > Total Appointments Available.

Demand_And_Capacity_Baseline_Date_Collection

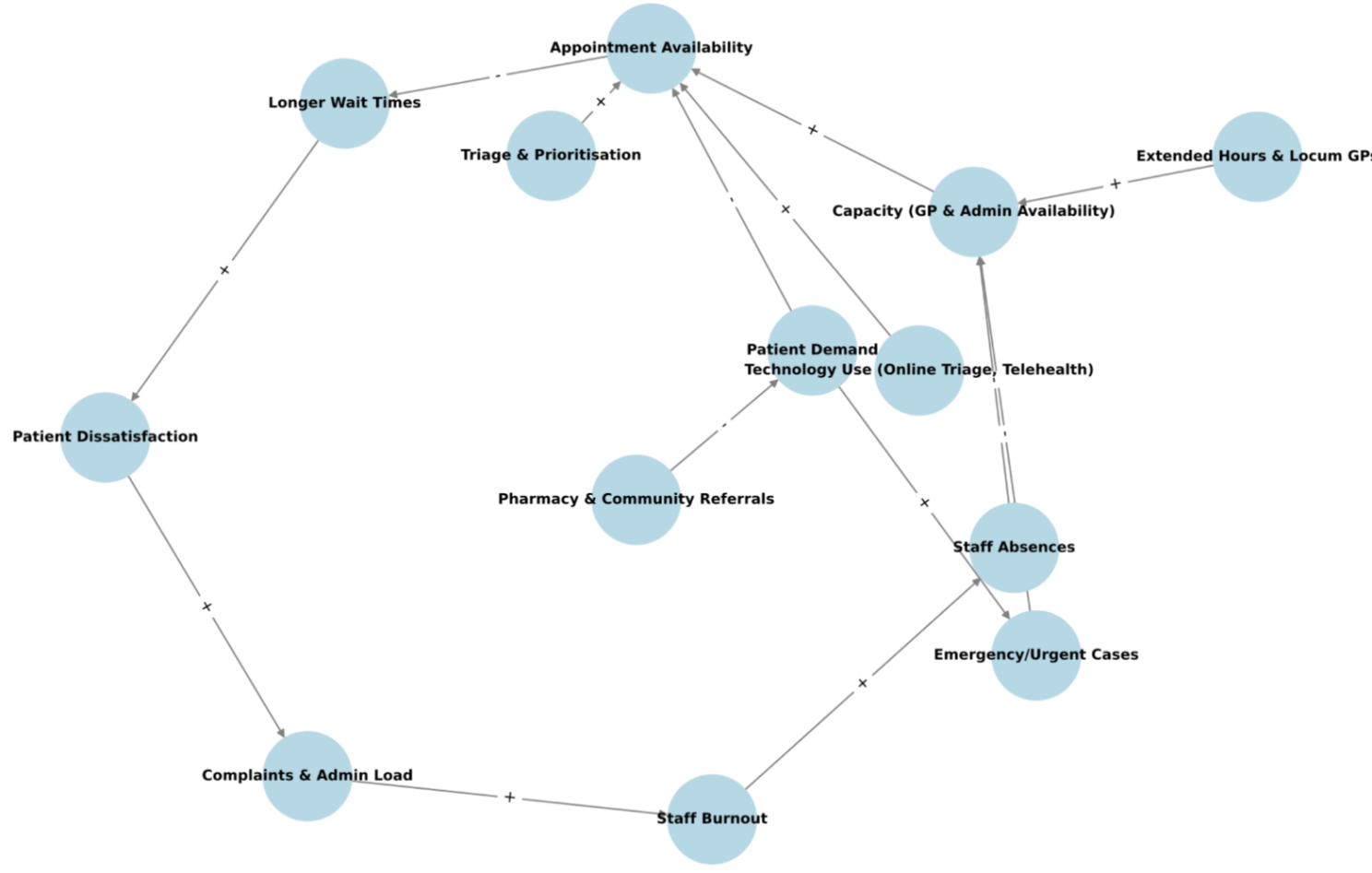

Chapter 6: Dynamic Systems Study: Predicting and Managing System Behaviour in Demand and Capacity analysis

Fig 4: Causal Loop Diagram Visualisation of System Dynamics

As a GP partner, understanding the interaction between demand and capacity during winter pressures is critical for maintaining service quality, patient safety, and staff well-being. Winter pressures often push the demand-capacity balance to its limits due to seasonal illnesses (flu, respiratory infections, COVID-19), workforce shortages, and increased patient complexity.

A dynamic system study explores how demand and capacity interact, whether the system self-corrects or deteriorates, and what forces drive successful or unsuccessful adaptation.

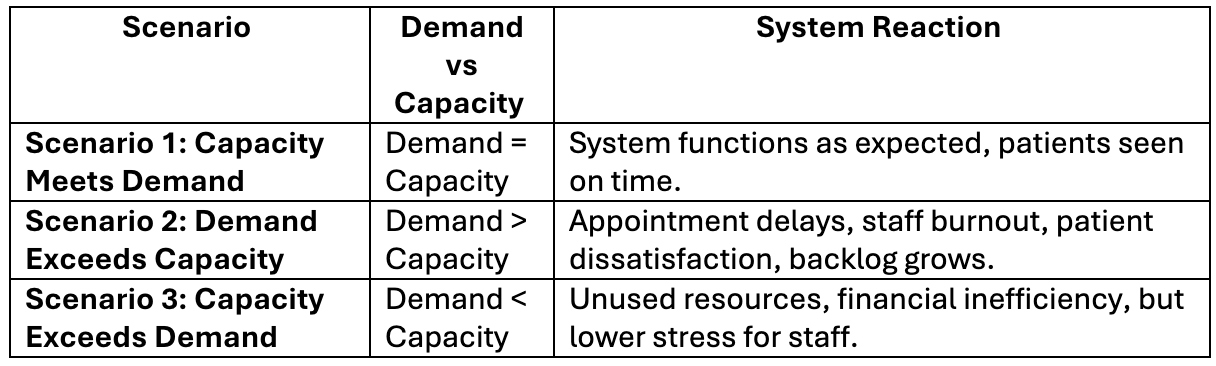

1. System Behaviour: How Demand and Capacity Interact in Winter Pressures?

Possible Scenarios

Key Winter Pressure Drivers That Influence Demand

- Increased Patient Illness: More flu, COVID-19, respiratory infections.

- Higher Staff Absences: Sickness, burnout, leave.

- Hospital Discharge Delays: Patients not moving out of secondary care fast enough means a redirection to primary care.

- Public Behaviour: Fear of hospital visits → more GP attendance.

Key Winter Pressure Drivers That Influence Capacity

- GP and Admin Staff Availability: Limited resilience in the workforce.

- Appointment Scheduling Efficiency: The ability to triage efficiently and effectively depends on the level training of the staff.

- Technology & Telehealth Use: Availability of online triage systems (e.g., eConsult, Klinik, Accurx, Hero Health etc ).

- External Support: NHS winter resilience funding, additional locums, pharmacy appointments.

2. System Response: Does the System Self-Correct?

Balancing Feedback Loops (Self-Correcting Mechanisms)

Triage & Prioritisation: Emergency cases seen first; routine cases deferred.

Extended Hours & Locum GPs: Temporary increase in capacity.

Pharmacy & Community Services Referrals: Additional capacity for diverting non-critical or some critical cases. For example, the availability of CCRT in some areas.

Use of Remote Consultations: Reducing face-to-face demand.

Negative Reinforcing Feedback Loops (Worsening the Crisis)

GP Burnout & Absenteeism: Overwork leads to more absences, reducing capacity further.

Longer Wait Times → More Urgent Cases: Delayed care worsens conditions, leading to more severe demand.

Patient Dissatisfaction → More Complaints: Increases admin workload, reducing efficiency.

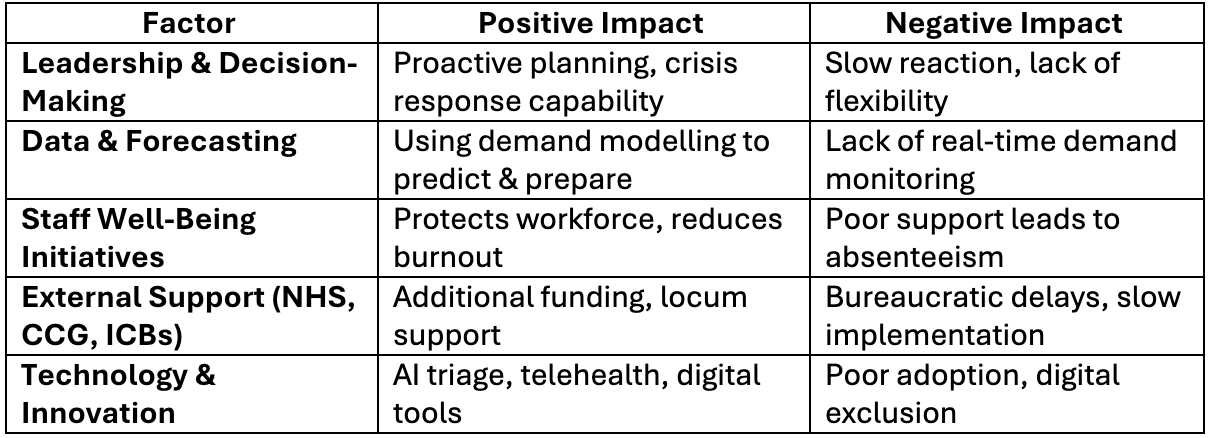

3. What is the Driving Force Behind the Practice’s Response?

Identifying Key Drivers Behind Practice Management

Critical factors influencing demand-capacity equilibrium include leadership decisions, workforce resilience, and NHS funding models.

4. What Determines Whether the System Fails or Adapts?

If balancing feedback loops (efficient triage, extended hours, technology) are strong, the system self-corrects.

If negative reinforcing feedback loops (burnout, delays, complaints) dominate, the system spirals into crisis.

The key driver behind success is leadership’s ability to predict demand, adapt workflows, and protect staff resilience.

Chapter 7: Leveraging AI, Policy changes and Future Innovations

Each practice can adopt an experiential learning cycle, and thinking in systems provides a framework for tackling the challenges of demand and capacity as well as other strategic opportunities within primary care. It has the potential to deliver efficiency and financial sustainability for the practice.

When the stated goal is to enhance practice efficiency and profitability, you should also not forget the altruistic goal that incentivises people to work within the primary care system. This invisible “stock” of the system influences staff behaviour, and aligning them with the projected goal of the total system means everyone is involved in meeting the practice challenges of demand and capacity.

Furthermore, with artificial intelligence entering the health space, AI tools can be leveraged to optimise scheduling, triage, demand forecasting, and workload distribution, improving efficiency in primary care. Read more here.

AI can also be used to enable strategic thinking within the practice to enhance decision-making, problem-solving and the development of strategies. It should be viewed as an ally and not an obstruction to better services.

While this type of technological advancement is not yet mainstream, in other to future-proof primary care, practices must embrace data-driven decision-making, dynamic workforce strategies, and continuous improvement models while continuing to explore future NHS policy adjustments to support sustainable primary care models.

I hope this provides an overview of how to apply systems thinking in primary care to enhance service delivery and sustainability of your practice.

Best wishes.

References

England, N. (2024). NHS England» How to align capacity with demand in general practice. [online] England.nhs.uk. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/how-to-align-capacity-with-demand-in-general-practice/

England, N. (2024). NHS England» How to improve telephone journeys in general practice. [online] England.nhs.uk. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/how-to-improve-telephone-journeys-in-general-practice/

Meadows, D.H. (2008). Thinking in systems. Illustrated edition ed. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Mehlmann-Wicks, J. (2023). Safe working in general practice. [online] The British Medical Association is the trade union and professional body for doctors in the UK. [online] Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/gp-practices/managing-workload/safe-working-in-general-practice/

Reddy, S. (2024). The Impact of AI on the Healthcare Workforce: Balancing Opportunities and Challenges. [online] HIMSS. Available at: https://gkc.himss.org/resources/impact-ai-healthcare-workforce-balancing-opportunities-and-challenges/

The British Medical Association. (2024). Daily working contacts – Safe working in general practice – BMA. [online] Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/gp-practices/managing-workload/safe-working-in-general-practice/daily-working-contacts/

Watkins, M. (2024). The Art of Strategic Thinking. Random House.