Introduction: Why Systems Thinking Matters Now

GP practices across the UK are facing an unprecedented challenge: demand is rising while capacity remains constrained. Wait times lengthen, staff burn out, and both patients and practitioners suffer. Yet some practices navigate these pressures more effectively than others. What’s their secret?

The answer lies not in working harder, but in thinking differently, specifically, in adopting a systems thinking approach to demand and capacity management.

This article presents a practical framework for understanding your practice as an interconnected system, where small strategic changes can create significant ripple effects. Whether you’re a GP partner managing financial sustainability, a practice manager optimising workflows, or a clinician seeking to improve patient care, systems thinking offers a roadmap through complexity.

Part 1: Understanding Primary Care as a Dynamic System

Your Practice Is a Business.

While the heart of general practice is patient care, the reality is that GP practices operate as businesses. GP partners hold contracts with NHS England, commissioned through Integrated Care Boards (ICBs). You manage budgets, negotiate contracts, handle staffing, and make investment decisions. Understanding the business mechanics of your practice is essential to fulfilling your clinical mission.

Primary Care in the UK is the first point of contact for most patients seeking medical attention. It plays a vital role in managing chronic conditions, preventive care, and acute illnesses.

The Core Challenge of Balancing Demand and Capacity

At its simplest, your practice faces a mathematical problem: patient demand must align with available capacity. When these fall out of balance, the consequences cascade:

Demand exceeds capacity: Wait times increase, urgent cases worsen, patient satisfaction drops, complaints rise, and staff experience moral distress.

Capacity exceeds demand: Resources are underutilised, financial sustainability weakens, and the practice may struggle to justify staffing levels.

The art of practice management lies in maintaining this balance dynamically across different services, times of day, and seasons, while the science provides the tools to measure, predict, and optimise.

The Knowledge Crisis in Primary Care

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: much of what makes GP practices function effectively exists as tacit knowledge in the minds of experienced partners and managers. As these GPs retire, this wisdom risks disappearing. Younger GPs, often burnt out and disillusioned, are increasingly reluctant to take on partnership roles.

Systems thinking offers a solution. By making implicit knowledge explicit through frameworks, data, and processes, practices can capture institutional wisdom and make it transferable. I believe that by teaching system thinking you will be augmenting intuition with structure.

Part 2: The Systems Thinking Framework

Core Systems in Primary Care

The best way to approach the primary care landscape is to think in systems.

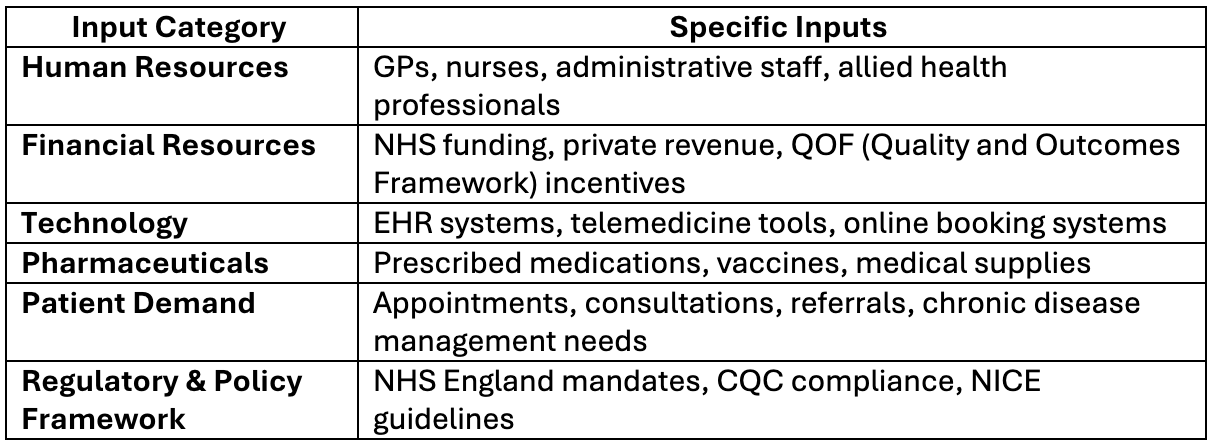

Every system, including your practice, consists of three fundamental elements:

Inputs are what enter your system: patient appointment requests, phone calls, e-consult submissions, prescription requests, referral letters, test results, and administrative queries. Inputs feed the system and enable it to function. Inputs are flows that enter the system—they’re the rate at which new things arrive or are added to the stocks. For example: Your rate of Workforce Retention. See the table below for more examples.

Processes are how you handle these inputs: your triage protocols, appointment scheduling logic, consultation workflows, prescription approval procedures, and administrative systems. These processes require Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)—documented, step-by-step instructions that ensure consistency and quality.

Outputs are the results: completed appointments, issued prescriptions, filed reports, satisfied patients, and sustainable workload for staff.

The quality of your outputs depends entirely on how well your processes transform inputs into desired outcomes.

Standard Operating Procedures

Without SOPs, your practice relies on individual memory and improvisation. This creates vulnerability when staff are absent or new people join; it can lead to a breakdown of consistency in the administrative, clinical, and operational workflows.

Consider two essential examples:

Appointment Scheduling SOP: How do you triage requests? What criteria determine urgency? Who can book emergency slots? What’s the escalation pathway when capacity is reached? How do you balance same-day demand with routine appointments?

Medication Refill SOP: How are repeat prescription requests logged? Do you know what safety checks happen? Who authorises non-routine requests? How quickly must these be processed? What happens when medications aren’t available?

Documenting these processes creates reliability and predictability.

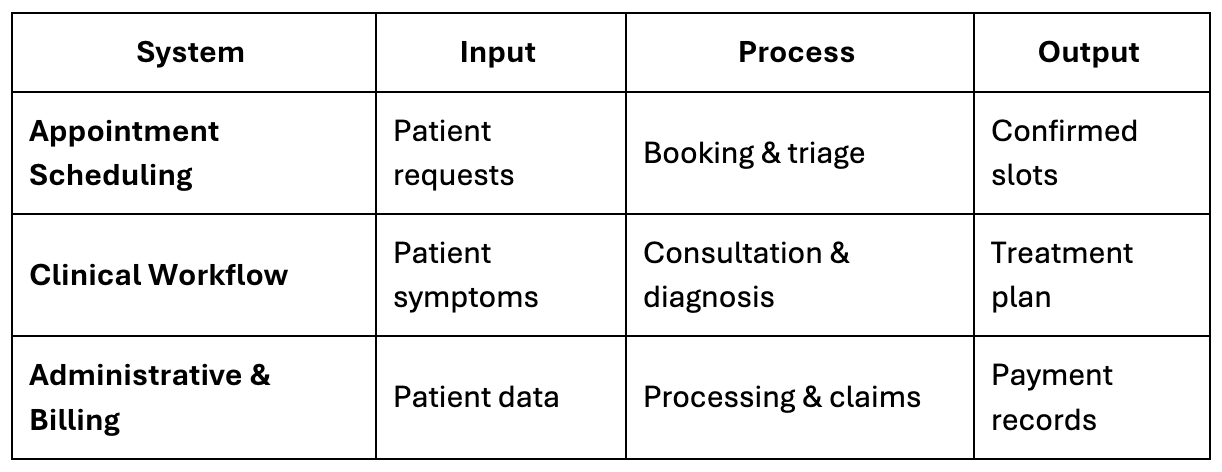

The Architecture of an Integrated Practice

Your Electronic Health Record (EHR), e.g SystmOne, EMIS, or another system, sits at the centre of a web of interconnected subsystems like Windows Drive Folders, Agilo Teamnet, and other third-party software. Optimising awareness about these systems and their interoperability will enhance the system thinking apparatus for your team. For example:

- Clinical systems: Triage, consultations, prescribing, referrals, test ordering and results management

- Administrative systems: Appointment booking, patient communications, record-keeping, document management

- Financial systems: Billing, payroll, resource allocation

- Compliance systems: CQC standards, safeguarding, information governance, clinical governance

- Human resource systems: Staff scheduling, training, performance management, wellbeing support

- Resilience systems: Business continuity planning, incident management, etc

The practices that thrive are those that have consciously designed how these systems/subsystems interact. The practices that struggle often have disconnected systems, creating inefficiency, duplication, and gaps.

Your task isn’t to create these systems from scratch, as most already exist in some form. Your task is to identify which systems are dormant or underoptimised, then activate, connect and refine them.

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it” – Peter Drucker

Here is a Systems Integration Flowchart illustrating how different primary care systems connect to create a profitable, efficient, and compliant general practice.

Fig. 1 Flowchart Illustration Showing System Integration

Part 3: Data-Driven Practice Management

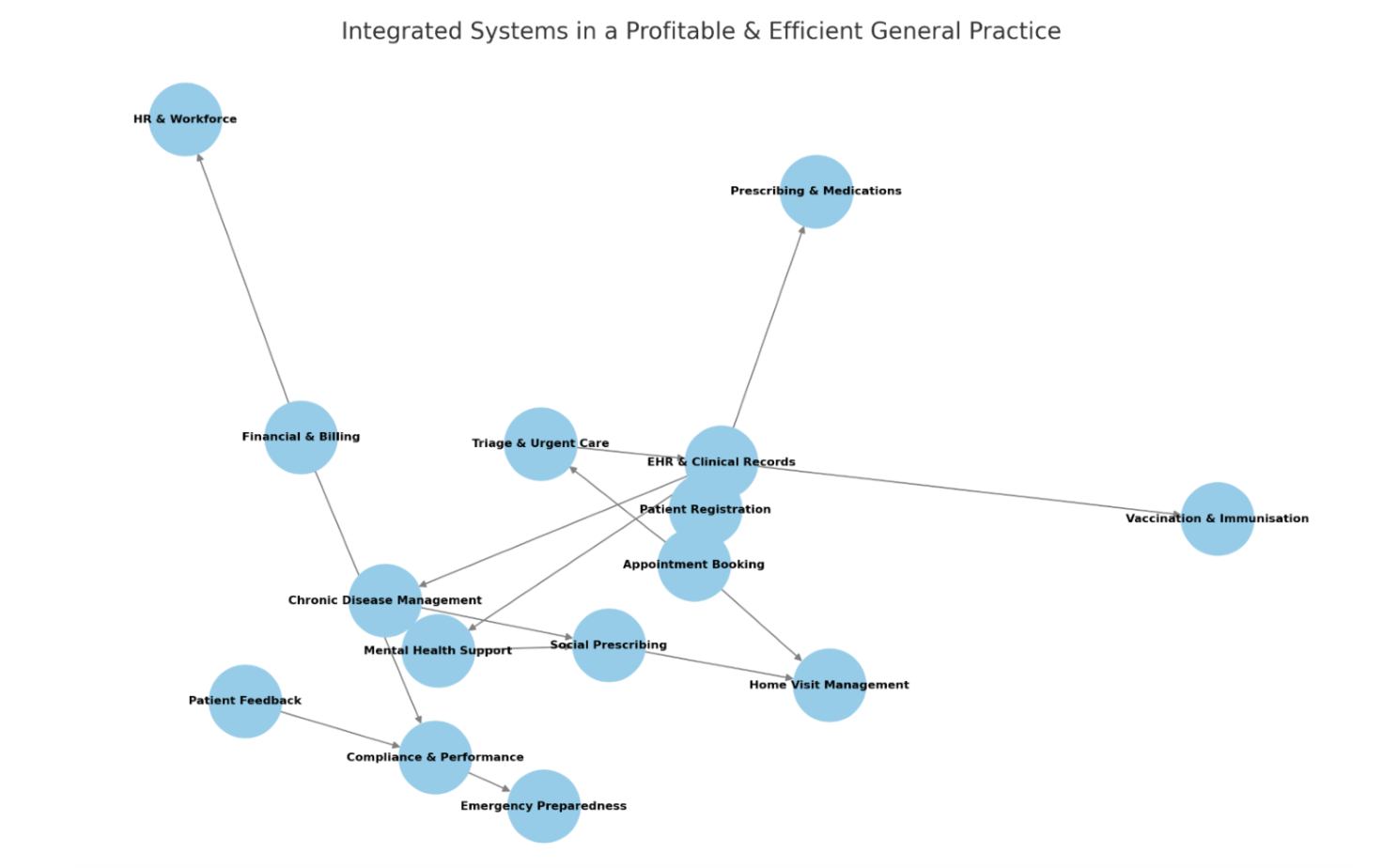

Without data, practice management becomes a guessing game. You sense that wait times are too long, you feel that staff are overwhelmed, you believe that certain times are busier—but feelings and beliefs don’t reveal root causes or measure improvement.

Data collection is integral to systems thinking.

Data transforms subjective impressions into objective insights. It reveals patterns invisible to individual experience, quantifies problems, and tracks whether interventions work.

Essential Data Points for Demand and Capacity Analysis

The new GMS contract requires GP surgeries to allow patients to send in health and administrative queries online throughout working hours starting from October 2025.

This means practices will need to keep their online consultation tools open for the duration of core hours (8am – 6:30pm) for non-urgent requests, including appointments, medication queries, and administrative requests.

This aims to free up phone lines and enable better triage of patients based on their medical needs.

To understand your practice’s dynamics, you need to systematically collect:

Demand Metrics:

- Total appointment requests (by type: routine, urgent, emergency)

- Phone call volume and duration

- Online booking and e-consult submissions

- Walk-in patient numbers

- Prescription requests

- Administrative queries

Capacity Metrics:

- Available GP hours and consultation slots

- Staff availability (including absences)

- Actual appointments delivered

- Consultation duration (planned vs. actual)

- Administrative staff capacity

Performance Metrics:

- Wait times (time from request to appointment)

- Unfulfilled requests (demand that exceeded capacity)

- Utilisation rates (percentage of available slots used)

- Did Not Attend (DNA) rates

- Patient satisfaction scores

- Staff satisfaction and wellbeing indicators

Benchmarking: What Does “Good” Look Like?

Benchmarking is a useful way of deciding what good looks like.

NHS contracts do not explicitly define performance thresholds for most demand and capacity indicators in primary care.

There are no contractual mandates specifying maximum acceptable waiting times for routine appointments, exact telephone response time targets, or specific capacity utilisation rates. This absence of explicit thresholds creates both a challenge and an opportunity.

Without clear targets, practices can struggle to know whether their performance is adequate or whether they’re falling behind. Conversely, practices have the flexibility to define meaningful benchmarks that reflect their unique context based on patient demographics, geography, staff composition, and local healthcare ecosystem.

While NHS contracts lack explicit numerical thresholds, professional guidance provides useful reference points:

The BMA recommends:

- Maximum 25 patient contacts per GP per day (for safety and sustainability)

- 15-minute appointment slots (to improve consultation quality and reduce repeat visits)

NHS England guidance emphasises:

- High-quality telephony systems to manage access effectively

- Data-driven capacity planning to identify and address demand-capacity mismatches

- Building robust data collection and analysis capabilities

- More recently, the drive toward total digital triage has created infrastructure that facilitates better data collection and analysis of demand and capacity patterns. Practices can now access several digital tools like Accurx, SystmConnect, and Klinik.

You can also develop in-house data collection templates on your respective EHR.

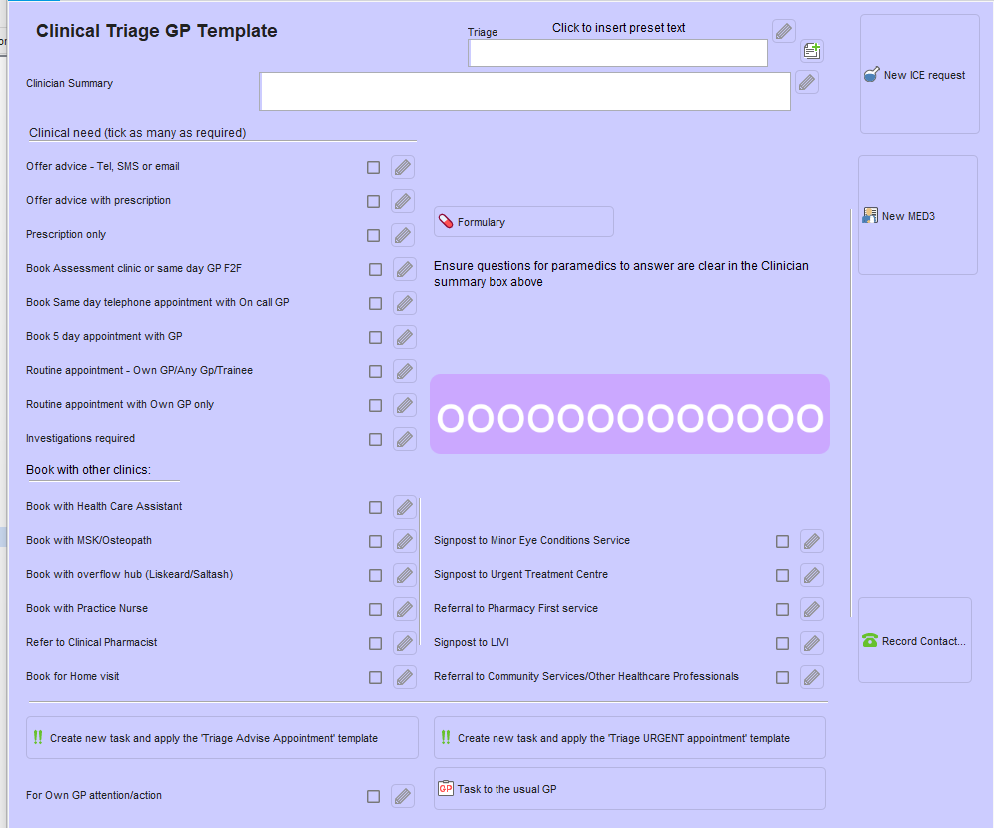

For example, a decision support template like the one shown below facilitates how clinicians may choose to process a triage, adding relevant codes to the SystmOne tabbed journal for the purpose of generating different types of reports, including appointment utilisation.

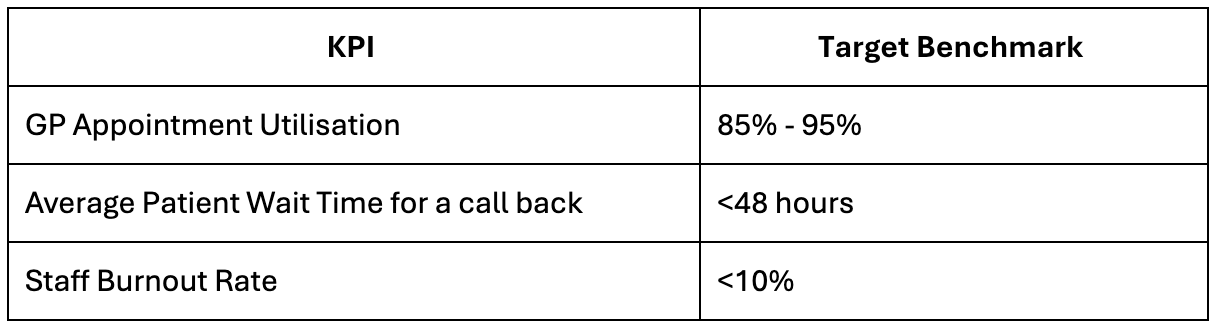

Establishing Your Practice-Specific KPIs

Given this landscape, each practice must take ownership of establishing its own Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). These should be:

Context-specific: Reflecting your patient population’s needs (a practice with many elderly patients will have different capacity needs than one serving primarily working-age adults)

Resource-aligned: Acknowledging your actual staff availability, physical infrastructure, and funding

Evidence-based: Grounded in your historical data showing what’s achievable and what indicates stress

Regularly reviewed: Adjusted in response to changing circumstances, contract modifications, and lessons learned

Collaboratively developed: Created in consultation with your local Integrated Care Board and other relevant health authorities

A practice with strategic KPI can set meaningful, achievable targets that drive genuine improvement rather than arbitrary benchmarks that don’t reflect your reality.

Your KPIs should track the efficiency and effectiveness of your practice operations while remaining honest about constraints you face.

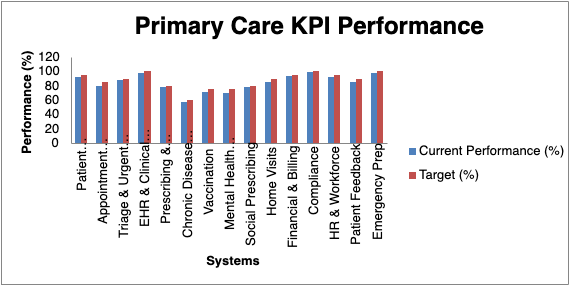

Building Your Performance Dashboard

Data sitting in spreadsheets doesn’t drive improvement. Visualisation makes patterns visible and creates accountability.

A well-designed dashboard should display:

- Real-time demand vs. capacity gaps

- Trend lines showing whether metrics are improving or deteriorating

- Peak demand periods (by day, time, season)

- Staff workload distribution

- Patient access metrics

- Financial performance indicators where appropriate

The goal isn’t to create beautiful graphs; it’s to stimulate productive conversations. When the practice team sees objective data, discussions shift from blame (“we’re overwhelmed because we’re short-staffed”) to problem-solving (“we have a capacity gap on Tuesday mornings—what options do we have?”).

Fig 2: Diagram of Sample Dashboard Visualisation

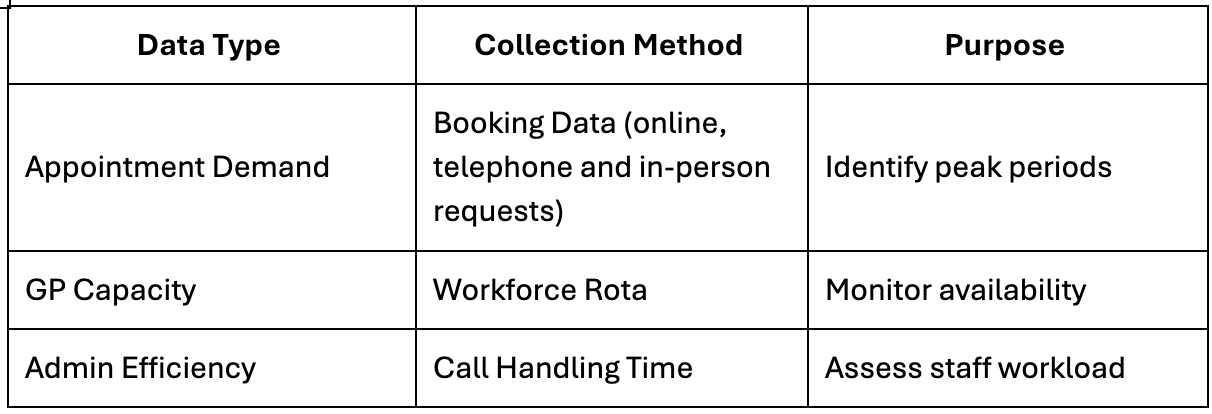

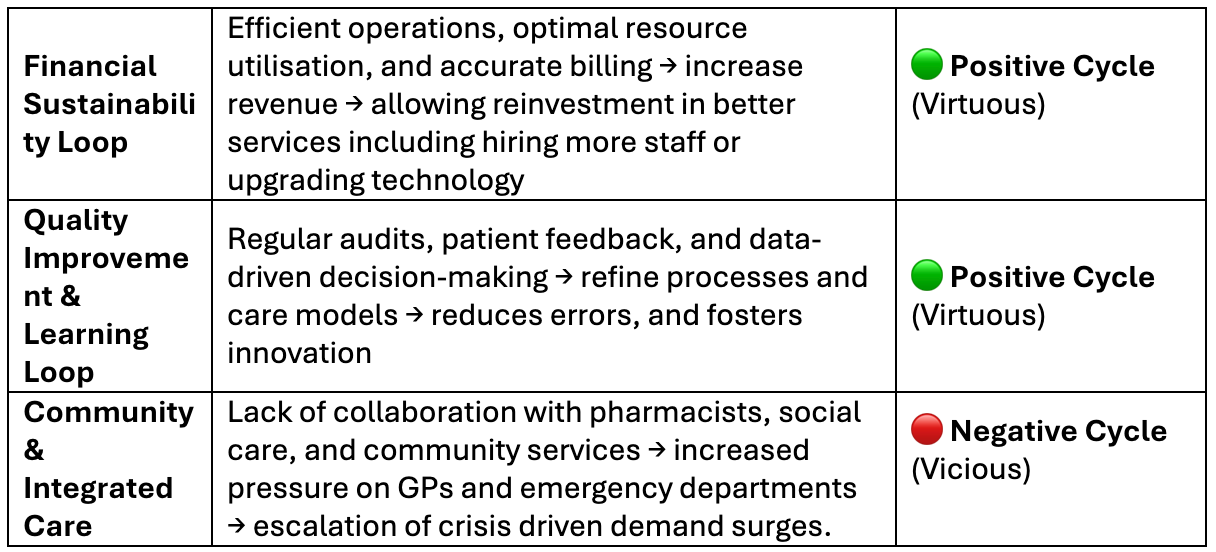

Feedback Loops

So far, we’ve discussed your practice as a collection of inputs, processes, and outputs—essentially a static picture. But practices don’t operate in still frames. They’re dynamic systems that respond and adapt over time.

This is where systems thinking becomes truly powerful: it helps us understand not just what’s happening, but how different parts of your practice influence each other in ongoing cycles. When you change one thing, ripple effects spread throughout the system. Sometimes these ripples amplify the change (making things better or worse faster than expected), and sometimes they dampen it (pushing back toward stability).

Understanding these dynamics requires grasping one crucial concept: feedback loops.

When an action produces results that influence the original action, it creates a circular chain of cause and effect. These loops are constantly operating in your practice, often invisibly, determining whether problems resolve themselves or spiral out of control.

Think of your practice like a thermostat system. When the temperature drops, the heating turns on. When it gets warm enough, the heating turns off. The system self-regulates through feedback. Your practice works similarly—but with far more complex and interconnected loops.

There are three main types of feedback loops shaping your practice:

Reinforcing Loops (Amplifying Change):

These loops accelerate trends in whichever direction they’re moving—creating either virtuous cycles (good things getting better) or vicious cycles (problems getting worse).

Example of a virtuous cycle: Better staff morale → higher quality patient interactions → more patient satisfaction → fewer complaints → less administrative stress → better staff morale → [cycle continues]

Each turn of the cycle strengthens the trend. Success breeds more success.

Example of a vicious cycle: Staff shortage → increased workload for remaining staff → burnout and sick leave → further staff shortage → [cycle worsens]

Each turn makes the problem worse. This is why workforce issues can deteriorate so rapidly—the feedback loop accelerates the decline.

(A) Reinforcing Feedback Loops (Amplify Change – “Vicious or Virtuous Cycles”, “Positively or Negatively” reinforcing the system)

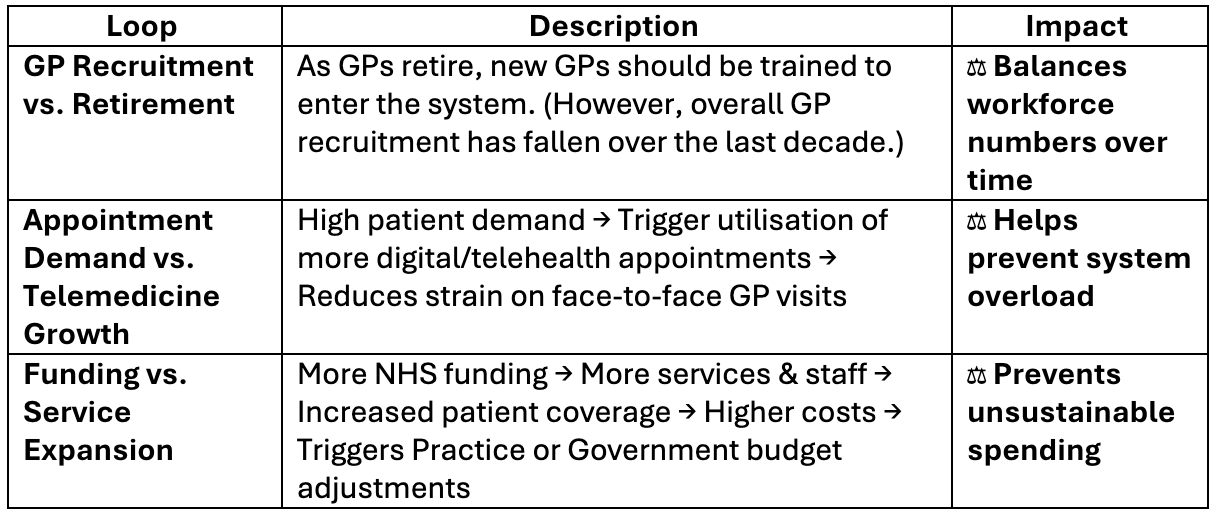

Balancing Loops (Self-Stabilising):

These loops push the system back toward equilibrium, acting as natural brakes that prevent runaway change.

Example: Long waiting lists → patient complaints increase → practice leadership responds by engaging locum clinicians → waiting times reduce → complaints decrease → system stabilizes

Balancing loops are your practice’s shock absorbers. They help you weather temporary surges without permanent damage.

(B) Balancing Feedback Loops (Stabilising – “Self-Correcting Systems”)

External/Regulatory Loops:

These are forces largely outside your control that still influence how your system behaves:

- NHS policy changes (new contract requirements, funding adjustments)

- Public health campaigns (changing patient awareness and expectations)

- Seasonal patterns (predictable winter demand, summer staffing)

- Local healthcare dynamics (hospital capacity affecting primary care demand)

(C) Regulatory & External Feedback Loops

Understanding which type of loop you’re dealing with is critical for effective intervention. Try to stop a reinforcing loop with a weak or token balancing intervention, and you’ll be frustrated when it fails. Reinforcing loops have momentum—breaking them requires interventions powerful enough to overcome their amplifying force.. Ignore a vicious cycle, and it will overwhelm your practice.

Let’s explore some examples

Example 1: The Staff Burnout Vicious Cycle (Reinforcing Loop)

The loop: Staff shortage → increased workload → burnout → sick leave → further staff shortage → [accelerating decline]

Weak balancing intervention that fails:

- Leadership sends a “wellbeing” email encouraging staff to “practice self-care”

- Result: The reinforcing loop continues—gestures don’t address the root cause

Strong balancing intervention that works:

- Hire locum GPs to immediately reduce workload

- Redistribute admin tasks to free up clinical time

- Implement protected time off that’s actually enforced

- Result: Breaks the cycle by genuinely reducing the pressure driving burnout

Example 2: The Patient Dissatisfaction Spiral (Reinforcing Loop)

The loop: Long waits → angry patients → more complaints → staff spend time handling complaints → less capacity → longer waits → [worsening spiral]

Weak balancing intervention that fails:

- Put up a poster asking patients to “be kind to staff”

- Send apology letters

- Result: Doesn’t address the capacity issue, spiral continues

Strong balancing intervention that works:

- Implement comprehensive digital triage to better match demand to capacity

- Add evening/weekend clinics temporarily

- Bring in additional administrative staff to handle complaints efficiently

- Result: Actually reduces wait times and breaks the cycle

Example 3: The Success Breeding Success (Positive Reinforcing Loop)

The loop: Good staff morale → better patient care → positive feedback → staff feel valued → even better morale → [virtuous cycle]

Inappropriate balancing intervention: If leadership sees morale is high and thinks “we can now push them harder” or cuts resources because “they’re managing fine”

- Result: You’ve just sabotaged your own success

Now let’s see how these feedback loops play out in real time during winter pressures—when your system faces its annual stress test.

Part 4: Case Study – Understanding System Dynamics During Winter Pressures

To truly grasp demand and capacity dynamics and apply your system thinking skills, let’s analyse how your practice responds during winter pressures. It is the annual stress test that reveals system strengths and vulnerabilities.

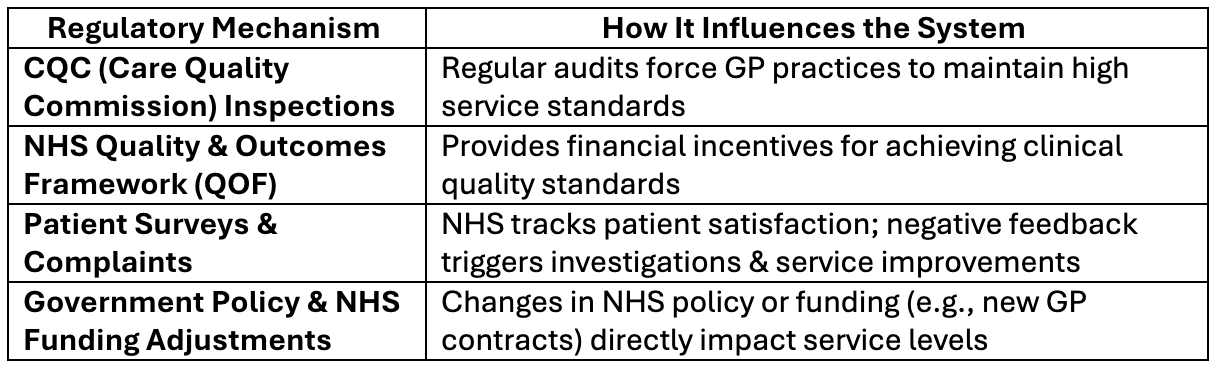

So far, we’ve discussed inputs, processes, and outputs—the flows through your system. But to fully understand system dynamics, we need to add another element: stocks—the accumulated resources that exist within your system at any given time. While inputs and outputs are about flow (measured as rates), stocks are about accumulation (measured as quantities).

System Stocks: Your Available Resources

Think of stocks as your practice’s accumulated resources:

- Human capital: Your GP workforce, nursing staff, administrative team, and their collective skills and capacity

- Physical capital: Consulting rooms, equipment, technology infrastructure

- Organisational capital: Your protocols, relationships, reputation, and institutional knowledge

- Financial capital: Your reserves, funding streams, and investment capacity

- Patient trust: The goodwill and confidence your community has in your practice

These stocks fluctuate. Staff leave or get sick, equipment fails, funding changes, and patient trust can erode or strengthen based on your performance.

Of all inputs, the GP and healthcare workforce is the most limited and critical. Here’s why:

- Supply shortage: GPs are retiring earlier due to burnout, and recruitment isn’t keeping pace

- Geographic disparities: Rural and underserved areas face severe recruitment challenges

- Demand growth: Aging populations and increased chronic disease complexity drive higher consultation needs

- Time constraints: Each GP has finite hours, and consultation quality suffers when rushed

When GP numbers fall below a critical threshold, the entire system degrades. Access deteriorates, emergency department attendance rises, patient satisfaction plummets, and remaining staff experience increased pressure, creating a vicious cycle. Practices are at risk of closure where recruitment is severe.

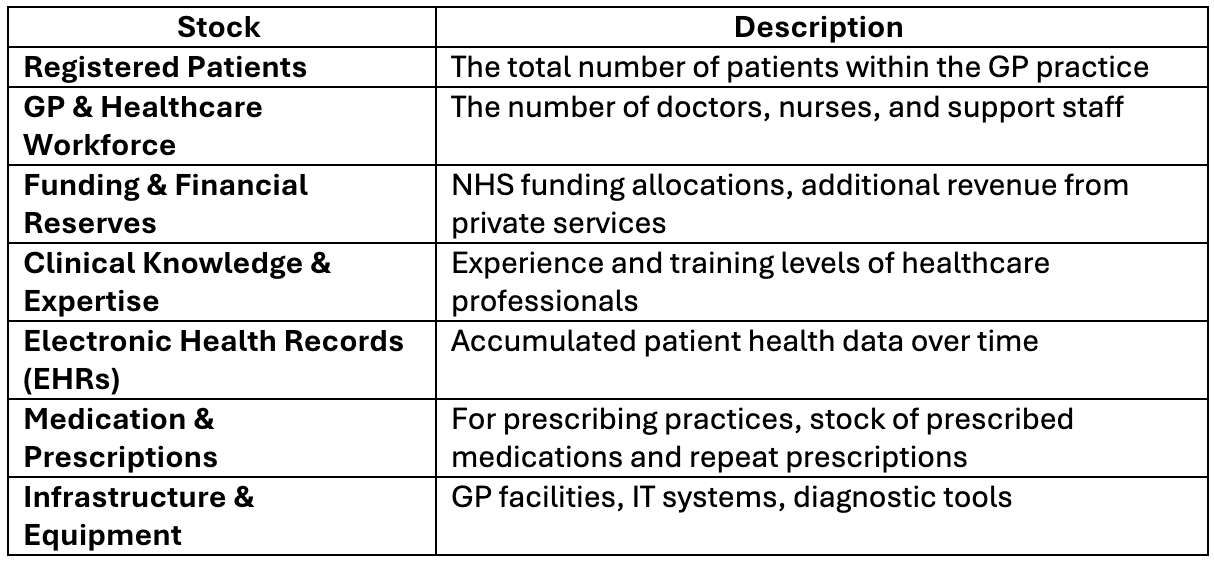

What is the Driving Force Behind the Practice’s Response during the Winter pressure?

Critical factors influencing demand-capacity equilibrium include leadership decisions, workforce resilience, and NHS funding models.

Let’s explore how these concepts can impact your practice during winter pressures.

Winter Pressures: A System Dynamics Analysis

Winter pressures emerge from predictable interactions:

Demand drivers intensify:

- Seasonal illness (flu, COVID-19, respiratory infections) increases consultation requests

- Vulnerable patients require more complex, time-intensive care

- Hospital discharge delays redirect patients back to primary care

- Public anxiety about accessing secondary care drives GP attendance up

Capacity constraints tighten:

- Staff absences rise (illness, exhaustion, annual leave)

- Remaining staff face higher workload intensity

- Technology systems may struggle under peak loads

- External support (locum availability, urgent care services) becomes stretched

The system’s response determines the outcome:

If balancing mechanisms are strong, the practice self-corrects:

- Efficient triage prioritises urgent cases

- Extended hours and locum GPs temporarily expand capacity

- Remote consultations reduce face-to-face burden

- Pharmacy and community service referrals divert appropriate cases

- Strong leadership maintains staff morale and adapts workflows

If negative reinforcing loops dominate, crisis spirals:

- Overworked staff become sick or leave

- Longer waits cause patient conditions to worsen, increasing urgency

- Rising complaints consume administrative capacity

- Staff morale collapses, further reducing effective capacity

- The practice enters a death spiral

Identifying Leverage Points

Systems thinking reveals that not all interventions are equally effective. Some actions have minimal impact; others create transformational change.

High-leverage interventions:

- Protecting staff wellbeing: Preventing burnout preserves your most critical resource

- Optimising triage: Matching patients to the right care level multiplies effective capacity

- Implementing robust SOPs: Reducing variability and errors frees cognitive resources

- Strategic technology adoption: AI triage, automated admin, and telemedicine can shift capacity curves

- Building organisational resilience: Systems that flex under pressure recover faster

Low-leverage interventions:

- Exhorting staff to “work harder” (rapidly hits diminishing returns and accelerates burnout)

- Adding isolated new services without system integration

- Reactive firefighting without addressing root causes

The key insight to take away is that workforce resilience is the fulcrum. Protect it, and your practice can weather storms. Neglect it, and your entire system becomes fragile.

Read more about how to measure practitioner wellbeing in primary care here.

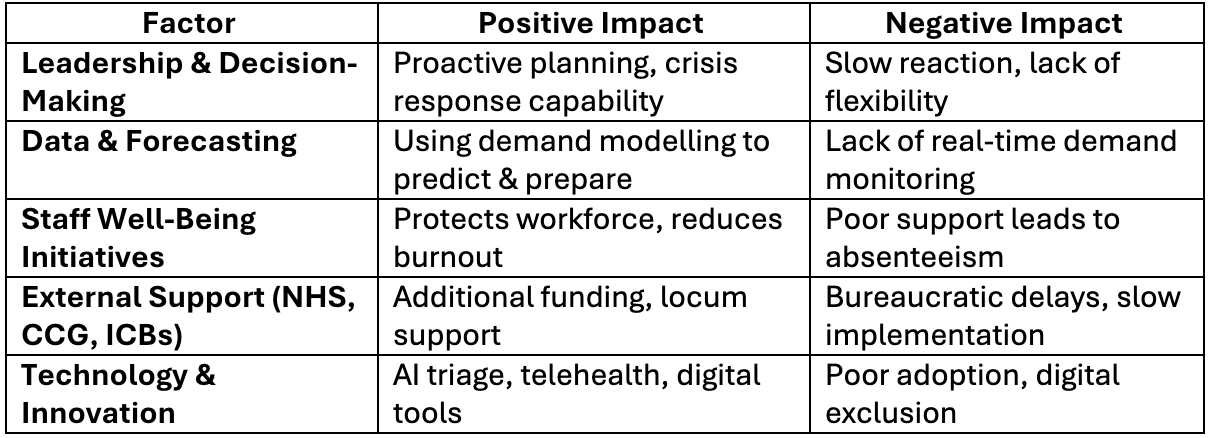

Fig 3: Causal Loop Diagram Showing Demand-Capacity Feedback Loops (Plus (+) adds to the item at the head of the arrow, while minus (-) takes away.

Fig 4: Causal Loop Diagram Visualisation of System Dynamics

Part 5: Quality Improvement in Practice—The PDSA Approach

Quality improvement activities are another tool to bring the theory of systems thinking into practice to effect measurable change.

Understanding systems is valuable, but improvement requires structured action. The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) methodology provides a disciplined framework for testing changes and learning what works.

Setting Clear Aims

Every quality improvement project needs a specific, measurable aim. For demand and capacity, an effective aim might be:

“To reduce the average wait time for routine appointments from 14 days to 7 days within 6 months, while maintaining same-day access for urgent cases and without increasing staff overtime.”

Notice the specificity: what will improve, by how much, by when, and with what constraints. Watch the video on HOW TO WRITE A GOOD AIM STATEMENT FOR YOUR QI PROJECT.

The Family of Measures

To track progress, you need three types of measures:

Outcome measures (Did the intervention achieve the desired result?):

- Average wait time for routine appointments

- Percentage of patients seen within target timeframes

- Patient satisfaction scores

- Staff wellbeing indicators

Process measures (Is the intervention being implemented as planned?):

- Number of patients triaged daily

- Percentage of appointments signposted

- Utilisation rate of new appointment slots

- Adherence to new SOPs

Balancing measures (Are there unintended negative consequences?):

- DNA rates (are patients less likely to attend different appointment types?)

- Clinical safety incidents

- Staff overtime hours

- Complexity of cases being deferred

All three are essential. Focusing only on outcome measures can miss implementation failures or create new problems elsewhere in the system.

The PDSA Cycle in Practice

Plan:

- Collect baseline data on current demand patterns and capacity constraints

- Identify peak pressure periods and bottlenecks

- Select a specific intervention to test (e.g., “Add a morning triage nurse appointment slot to handle minor acute respiratory cases”)

- Predict what should happen if the intervention works

Do:

- Implement the change on a small scale (e.g stagger the implementation timeline, use one location at time)

- Document exactly what happens

- Track your process and outcome measures in real-time

- Gather qualitative feedback from staff and patients

Study:

- Compare before-and-after data

- Analyse whether the intervention worked as expected

- Identify unexpected consequences (positive or negative)

- Understand why results occurred, not just what happened

Act:

- If successful, scale the intervention across the practice

- If unsuccessful, either modify and test again, or abandon and try a different approach

- If partially successful, refine and iterate

- Document learnings for organisational memory

Practical Example: Optimising Digital Triage Usage

Observation: Your patients contact the practice in a variety of format, however, you wish to align your practice to handle total digital triage in line with contractual requirements.

Plan: Collect the number of daily requests and the nature of requests. Identify staff training needs. and current staff capacity. Aim to be fully operational with total triage by the set contractual date.

Do: Offer staff training, stagger implementation to manage adoption, track patient contact formats, triage outcomes, patient feedback, and GP workload, DNA rates etc

Study: Data shows the increased digital triage uptake by staff and patients. Review DNA rates for appointments offered. Review patient and staff feedback about any tools that were introduced.

Act: For example – Scale the intervention but add clearer patient communication about appointments and implement reminder SMS for these slots to reduce DNAs, Redesign appointment ledgers based on feedback, etc.

Then start the cycle again with refinements.

Data Collection Tools

Systematic data collection is essential. Some of the Total triage tools have built-in data analysis tabs. A simple Excel template can also be used to present data.

This data becomes your evidence base for improvement

Demand_And_Capacity_Baseline_Date_Collection

Part 6: The Bigger Picture—Policy, Technology, and the Future

Beyond Individual Practice Optimisation

While improving your own practice is essential, it’s worth acknowledging the broader context. Primary care faces structural challenges that individual practices cannot solve alone:

- Funding models that don’t fully reflect complexity and demand

- Workforce pipelines that aren’t producing enough GPs

- System integration gaps between primary, secondary, and social care

- Policy volatility that makes long-term planning difficult

Effective advocacy for better policy requires practices to demonstrate what works and what doesn’t, which brings us back to data and systems thinking.

The AI Revolution: Is It A Threat or an Opportunity?

Artificial intelligence is entering healthcare rapidly, and primary care will be transformed. The question isn’t whether AI will change your practice, but how you’ll shape that change.

However, let’s be clear about where we actually are versus where we’re heading. Much of the AI revolution in primary care is still aspirational rather than operational.

What’s actually in use in UK GP practices now:

Current adoption is modest. About a quarter of GPs report using any AI tools in clinical practice as of 2024-2025. The tools that have gained traction focus on:

- AI medical scribes and documentation: Tools like Heidi, Hepian Write, and Tortus that transcribe and summarize consultations, reducing GP administrative burden (this is the most common application)

- Administrative automation: Enhanced online booking through NHS App, basic appointment scheduling optimization

- Triage support: Digital triage platforms (though many aren’t truly AI-powered—they’re rule-based algorithms)

- Clinical decision support: Emerging tools that flag potential diagnoses or drug interactions, though adoption remains limited

What’s being piloted or planned (but not yet mainstream):

NHS England is procuring a £180 million AI framework that includes predictive analytics capabilities for forecasting patient volumes and optimising staffing, but this is still in the planning and procurement phase.

Sophisticated demand forecasting using historical patterns, weather data, and epidemiological modeling exists primarily in secondary care settings. For example, NHS England has deployed A&E demand forecasting tools that predict emergency admissions three weeks ahead. These capabilities haven’t yet migrated to primary care at scale.

What are the near-future capabilities?

As these technologies mature and NHS infrastructure develops, expect to see:

- Predictive capacity planning: AI systems that analyze your practice’s historical data alongside population health trends to forecast demand spikes

- Intelligent workflow optimisation: Tools that dynamically adjust appointment scheduling based on real-time demand patterns

- Enhanced clinical decision support: More sophisticated systems that integrate patient records with latest evidence to suggest diagnostic and treatment pathways

- Proactive patient outreach: AI identifying patients who would benefit from preventive interventions before they become acute

What are the Strategic AI applications that are already valuable?:

Beyond clinical tools, AI can enhance practice management right now through:

- Data analysis: Using AI to identify patterns in your demand and capacity data that human analysis might miss

- Strategic thinking support: Leveraging AI (like this conversation) to explore scenarios, test assumptions, and develop improvement strategies

- Policy and literature review: AI can rapidly synthesise guidance documents, research, and best practices to inform decision-making

The key is approaching AI as an ally, not a threat. AI won’t replace GPs; our human judgment, empathy, therapeutic relationships, and ethical reasoning remain irreplaceable. But AI can handle routine cognitive tasks, process information faster, and augment human capabilities.

Critical considerations for AI adoption:

- Start with clear problems: Don’t adopt AI because it’s trendy. Identify specific pain points (documentation burden, capacity planning, triage bottlenecks, patient risk stratification) and find tools that address them

- Pilot before scaling: Test AI tools with a small group, measure impact, gather feedback, then decide whether to expand

- Maintain clinical governance: AI suggestions require human verification, so establish clear protocols for oversight

- Protect patient trust: Be transparent with patients about AI use and ensure data privacy

- Support staff adaptation: Training and change management are essential. AI adoption fails when imposed without staff buy-in

Practices that thoughtfully embrace AI will gain competitive advantages in efficiency, quality, and staff satisfaction. Those that resist risk falling behind as patient expectations and NHS requirements evolve. On the flip side, rushed AI adoption without proper planning, training, and governance creates new problems rather than solving existing ones.

The Human Element: Don’t Lose Sight of Why

In this article, we’ve focused on systems, data, and optimisation. At the heart of why all this is relevant is the invisible “stock” that powers everything: purpose.

Most people enter a career in primary care because they want to help patients and serve their communities. This altruistic motivation is a resource that can be depleted or replenished.

When practice management focuses solely on efficiency and profitability, staff feel like cogs in a machine. When it balances operational excellence with meaningful patient care and staff wellbeing, people thrive.

Practical ways to preserve purpose:

- Regularly share positive patient outcomes and stories with the team

- Involve staff in improvement projects—they have insights and value being heard

- Celebrate small wins, not just financial metrics

- Protect time for the kinds of patient interactions that remind clinicians why they chose this profession

- Make staff wellbeing a KPI equal in importance to patient access

A practice that optimises systems while neglecting staff morale will fail. A practice that nurtures both creates a virtuous cycle.

Conclusion: Your Systems Thinking Journey

Primary care is complex, pressured, and sometimes overwhelming. But complexity isn’t chaos, it’s pattern. Understanding those patterns through systems thinking empowers you to work with the forces shaping your practice rather than against them.

The journey starts with small steps:

- Map your current system: What are your inputs, processes, and outputs? Where do bottlenecks occur?

- Start collecting data: You can’t improve what you don’t measure

- Document one SOP: Begin creating organisational knowledge that transcends individual people

- Run one PDSA cycle: Test a small change, learn from it, iterate

- Identify one leverage point: Where could a small change create disproportionate benefit?

You don’t need to transform everything overnight. Systems change gradually, and small improvements compound over time.

Remember:

- Your practice is a system, not a collection of disconnected parts

- Data reveals patterns that experience alone cannot

- Feedback loops amplify both successes and failures; learn what they are.

- Your workforce is your most critical and fragile resource: protect it

- Technology is a tool, not a solution; use it thoughtfully

- Purpose matters as much as efficiency

The practices that will thrive in the coming decades aren’t those that work hardest; they’re those that think most clearly about their systems, use data to guide decisions, and balance operational excellence with human flourishing.

Systems thinking won’t solve all your problems. But it will give you a map through complexity, a language to discuss challenges clearly, and a framework to turn insights into action.

Your patients deserve better access. Your staff deserve sustainable workload. Your practice deserves financial stability. Systems thinking can help you achieve all three.

I hope this provides an overview of how to apply systems thinking in primary care to enhance service delivery and sustainability of your practice.

Best wishes.

References

England, N. (2024). NHS England» How to align capacity with demand in general practice. [online] England.nhs.uk. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/how-to-align-capacity-with-demand-in-general-practice/

England, N. (2024). NHS England» How to improve telephone journeys in general practice. [online] England.nhs.uk. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/how-to-improve-telephone-journeys-in-general-practice/

Meadows, D.H. (2008). Thinking in systems. Illustrated edition ed. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Mehlmann-Wicks, J. (2023). Safe working in general practice. [online] The British Medical Association is the trade union and professional body for doctors in the UK. [online] Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/gp-practices/managing-workload/safe-working-in-general-practice/

Reddy, S. (2024). The Impact of AI on the Healthcare Workforce: Balancing Opportunities and Challenges. [online] HIMSS. Available at: https://gkc.himss.org/resources/impact-ai-healthcare-workforce-balancing-opportunities-and-challenges/

The British Medical Association. (2024). Daily working contacts – Safe working in general practice – BMA. [online] Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/gp-practices/managing-workload/safe-working-in-general-practice/daily-working-contacts/

Watkins, M. (2024). The Art of Strategic Thinking. Random House.