A fundamental principle of quality improvement is establishing a set of measures to determine when an improvement has been successful. These are referred to as outcome measures. We can also measure how the system works to achieve a certain outcome; this is called process measures.

If we take this approach to primary care, how can we measure success or failure in Primary Care?

In a hospital setting, key metrics often include safety measures, the number of inpatient falls, and the frequency of certain hospital-acquired infections.

In primary care, what metrics should we focus on? For example, how quickly do patients receive appointments when they need them? Additionally, how many cancer diagnoses are being detected in primary care? Are our high-risk patients receiving timely reviews in the community to identify when they are deteriorating?

There are also systemic factors to consider. How well-connected are the community teams? Are the care pathways meeting the needs of patients, and how satisfied are our patients with the services they have received?

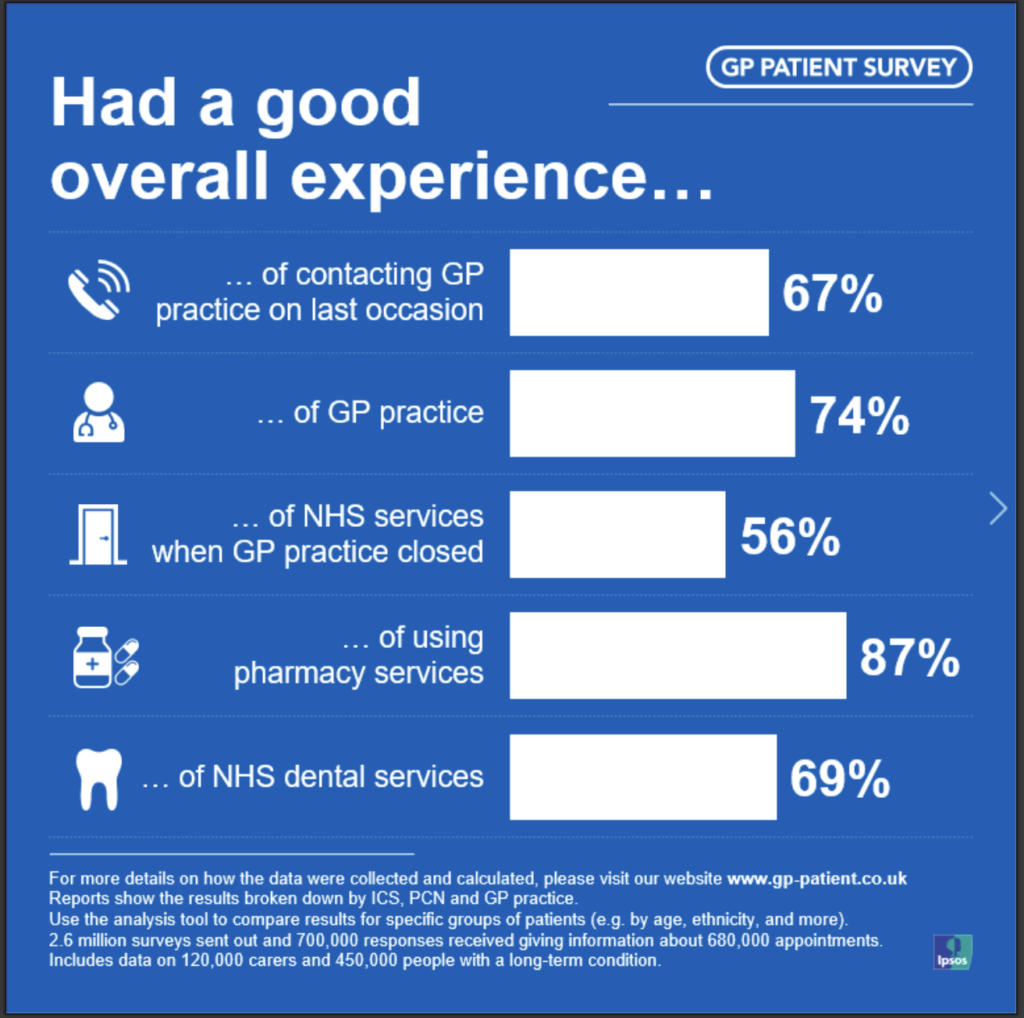

We can answer some of these questions by looking at the available metrics from the GP Patient Survey and Data on GP appointments. Their analysis indicates that GP surgeries are providing a record number of appointments. Hopefully, this increased capacity is serving those who truly need it. Furthermore, the majority of patients reported high levels of satisfaction with the service they received when they contacted their GP, feeling that their needs were effectively met.

Each practice can look at the performance of their PCN using the Power BI dashboard on the 2024 GP patient survey website here.

However, many aspects of primary care activities are difficult to quantify. It’s challenging to outline process measures for factors such as the social determinants of health, which can add complexity and may hinder our ability to gauge success in managing a patient’s overall health. As a result, these patients might end up in the hospital for reasons that regular appointments at the surgery cannot foresee. Some of our medically complex patients are likely to bypass the surgery and seek help from secondary care directly. Should we consider it a failure when this happens?

The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) is a system that rewards general practices in England for providing high-quality care to their patients, which can lead to better health outcomes for patients. The QOF is often criticised as being restrictive in its reporting domains, lacking the ability to evaluate important dimensions of quality of care, and its future is uncertain. (Majeed and Molokhia, 2023)

It certainly needs refining to capture primary activities that are not particularly related to specific diseases.

One type of measure that is often overlooked during a quality improvement is called a balancing measure.

A balancing measure can help answer the question, “Are we creating issues within our system?” For instance, are we hiring too many staff or too few? By conducting regular financial reviews of the services provided, we can gain insight into a general practice’s profitability and overall viability. This information can guide decision-making and ensure the practice is headed in the right direction.

As primary care clinicians, we should not rely solely on numbers to measure our success or failure. The effort we put forth each day for our staff and the patients in front of us is just as important. This includes being a listening ear for a distressed patient, supporting the well-being of our staff and ending each day with a smile, knowing that we did our best and will strive to do the same tomorrow.

Primary care is invaluable to the healthcare ecosystem and long-term patient health outcomes. Support for primary care must reflect our value for and understanding of how it functions. Read more about a radical vision for primary care here.